Studio Egret West are the company responsible for what has become one of Stratford’s most recognisable landmarks. This is what they had to say about the project:

The Stratford Shoal

Studio Egret West is delighted to announce the completion of ‘The Stratford Shoal’, a 250m titanium sculpture in Stratford, London.

The Shoal is a public realm intervention, which aims to improve the urban continuity and legibility of the existing 1970’s Stratford Centre. In the 70’s, the Stratford Centre was created with a positive frontage to the existing high street to it’s south. With the introduction of the Stratford bus interchange, and later, the refurbishment of Stratford Station to the north, the ‘back’ of the centre, with its delivery bays and car parking ramps, became much more visibly public. Recently, the Olympic Park and the Westfield Centre entrances have been established to the north meaning that the ‘back’ has very much become the front: the entrance to Stratford.

In 2009 a competition was established by London Borough of Newham to suggest a solution to this complex urban problem, which was won by Studio Egret West.

Studio Egret West responded to Newham’s desire to emphasise the Stratford Centre entrance with a bold and innovative approach.

A series of curvaceous and branch-like steel ‘trees’ are arranged with a trellis like array of support points. On these are fixed giant leaf shapes of titanium that glisten in the light and are able to move in the wind. Early on, an option to intensively plant mature trees around the sites edge was investigated, but was not pursued due to the myriad of vital services running beneath the existing pavement.

The surface of giant ‘leaves’ mimics the scale and rhythm of the existing trees and re-establishes the urban continuity of the site. They rise and deform, to mark and celebrate the entrance to the Stratford Centre and continue on, beyond, to the old high street. They are an indicator that Stratford is not just the home of the Olympics and has a much broader offer.

The leaves also provide a screen for the assortment of Stratford Centre buildings behind. Rather than hiding this elevation behind, the leaves act to enliven it, divert attention from it and playfully raise the spirits of its onlookers, rising and falling with the choreographic elegance of a shoal of fish.

With the view of semi-permanency rather than a temporary intervention, a light and durable material was sought for the leaves. Titanium offered both durability and lightness and held the additional trump card of being able to alter its colour through anodising.

The Shoal uses the breadth of this technology to adjust its tone dependant on location with the leaves shifting from warm reds near the cultural quarter, bright yellows and gold’s around the main entrance to the Stratford Centre and pedestrian crossing; and blue tones which compliment the green hues of the existing trees.

The Stratford Centre has now started a process of reinvention and transformation, and will radically change over the coming 30 years. The Shoal allows the emerging plans for Stratford to take shape with a new titanium veil in the foreground, like a grandiose shimmering palisade, the Shoal plays a positive role in anchoring this place as it re-emerges confidently after the Olympics.

Sir Robin Wales, Mayor of Newham said:

“Newham is undergoing unprecedented transformation, nowhere more so than in Stratford. The Shoal is part of the £13.5 million high quality public realm project to improve Stratford Town Centre for residents and businesses and offer a unique visitor experience.

With the emergence of the Olympic Park and Westfield Stratford City, the Shoal will connect Stratford’s exciting new developments with the existing thriving town centre and cultural quarter, helping to position the area as a world leading business, leisure and tourism destination.”

David West, Studio Egret West said:

“The Shoal was born of a desire to turn a negative into a positive. Instead of screening the back of house of the Stratford shopping centre, which now finds itself in the foreground, we have created a playful and dynamic edge that brings a moment of delight to those arriving in Newham. We specifically used titanium because of its range of colours and its shimmering quality, meaning that the Shoal’s appearance constantly changes in response to varying light conditions”.

Technical Information

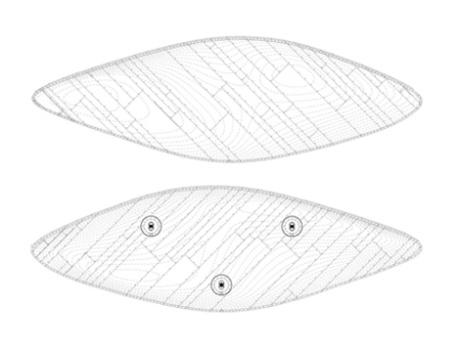

The Shoal was designed and manufacturered utilising the latest 3D technology, harnessing Rhino and 3D Microstation for it’s design and using CAD CAM technology for rapid prototyping and the manufacturer of it’s GRP leaves. The project’s use of BIM allowed the design team, with Studio Egret West as Architects and Packman Lucas as Engineer’s, to converse fluently with the contractor on the complex steelwork structure as well as the undulating and complex amorphous forms of the leaves. The computer model was not just used to build the forms but was also critical in testing motion, the leaves centre of gravity and the laying of the leaves single curved titanium strips over their double curved surface.

The 3D CAD model was central to the design and manufacturing process, used from the project’s inception as an iterative architectural and structural 3D design tool and evolving into a contractual ‘document’ used for production information, cost management and construction.

In tandem with this computer aided process was a much more ‘hand made’ approach. Prototyping the leaves at various scales, a number of times to test if the computer models were producing the correct ‘real-life’ results.

The steelwork was conceived as a series of treelike branches budding from a cluster or trunk, fabricated from a fixed number of radii and straight elements to create a modular set of repeatable components, which would appear to be completely random. The computer gave the designers many economies in fabrication and simplified the manufacturing process. The trunks were welded to form rigid composite elements and branches were fixed as they touched to add stability and to prevent buckling; in many ways behaving in a similar fashion to the structure of a tree.

Below ground are large complex base elements, comprised of composite steel I-beams and flats which reduce the moment forces of the trunks as they are transferred into their foundations. These elements had to work especially hard to make up for the foundations not being situated in their ideal positions but being defined instead by the myriad of underground services running below the pavement.

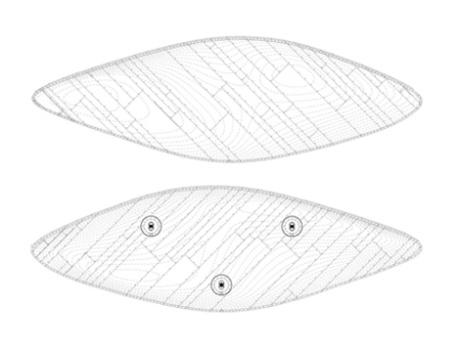

From the steelwork frame ‘bull-horn’ arms extend, each supporting one of 73 titanium clad GRP leaves. These arms are like wishbones, which connect the frame to the leaves and are intended to be as slim and elegant as possible, slimming to just 40mm where they penetrate into the rear of the leaves.

The leaves are manufactured from a thin GRP inner shell over a plywood structural frame, made from three moulds to give three varying forms, this strengthens the overall reading of the leaves as one surface. The leaf arms are fixed into the plywood frames with a hook detail allowing the leaves to be easily installed. At the end of this hook is a specialist bearing, which gives the leaves horizontal tolerance, ensuring they can hang freely. At the junction of the leaf arms is a rigid moulded plastic cowl (brightly coloured) and a soft rubber gaiter (similar to the leather gear stick gaiters found in cars). Again, all of these components were designed and manufactured directly from 3D CAD information.

It was critical from the outset of the project that the leaves had a hand made and crafted quality. Through prototyping a manufacturing process was developed which would deliver the qualities sought.

By testing fabrication methods the designers determined a specific laying pattern for the titanium strips on each of the leaves (placing thinner and shorter strips in areas of greater curvature and placing darker shades of colour in the deeper areas to further extend the sense of curvature).

By cladding the leaves in anodised titanium strips, the designers were able to optimise the effect of the leaves movement. Using an opalescent material to enhance the shimmering quality of the sculpture. Each titanium strip on each leaf was given an individual code, ensuring that each of the leaves was individual in pattern and colour.

At the rear of each leaf is a bi-directional damping mechanism, fixed to the leaves with a bespoke 3-dimensional bearing. The dampers allow the leaf’s to move for a limited range of motion and damp the movement as the forces, caused by the wind, increase. This collection of dampers, springs and bearings is designed to be dynamic, meaning that the greater the winds force the greater the dampers response.